http://blog.allelebiotech.com/2013/04/the-development-of-mneongreen/

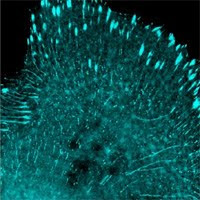

This week our most recent publication, “A bright monomeric green

fluorescent protein derived from Branchiostoma lanceolatum” will be

published in Nature Methods. It has already been viewable online for

some time now, here is a link.

We believe this new protein possesses a great deal of potential to

advance the imaging fields through enhanced fluorescent microscopy.

mNeonGreen enables numerous super resolution imaging techniques and

allows for greater clarity and insight into one’s research. As a result

of this we are taking a new approach at Allele for distribution of this

protein, and here we will describe the history of the protein and some

of the factors that led us down this path.

mNeonGreen was developed by Dr. Nathan Shaner at Allele Biotechnology

and the Scintillon Institute through the directed evolution of a

yellow fluorescent protein we offer called LanYFP. LanYFP is a super

bright yellow fluorescent protein derived from the Lancelet fish

species, characterized by its very high quantum yield, however, in its

native state LanYFP is tetrameric. Dr. Shaner was able to monomerize

the protein and enhance a number of beneficial properties such as

photostability and maturation time. The result is a protein that

performs very well in a number of applications, but is also backwards

compatible with and equipment for GFP imaging.

Upon publication there was a question of how distribution should be

structured. How would we make this protein available to researchers in a

simple manner was a very difficult challenge. We also relied heavily

on Dr. Shaner’s knowledge and experience in these matters, as he related

his experiences to us from his time in Roger Tsien’s lab at UCSD. When

the mFruits was published their lab was inundated with requests. The

average waiting period was 3 months to receive a protein and they

required a dedicated research technician to handle this process.

Eventually the mFruits from the Tsien lab were almost exclusively

offered through Clontech. Thus we decided that Allele Biotechnology

would handle the protein distribution and take a commercial approach to

drastically decrease the turnaround time. The next challenge we faced

was how to charge for this protein. Due to the cost of developing this

protein, which was fully funded by Allele, there is a necessity to

recoup our investment and ideally justify further development of

research tools, but we also understand the budget constraints every lab

now faces. From this line of thinking we conceived our group licensing

model; we wanted to limit the charge to $100 per lab. The way this is

fiscally justifiable is having every lab in a department or site license

the protein at this charge, including access to all related plasmids

made by us as well as those generated by other licensed users (Click here for our licensing page).

The benefit we see to this is that the protein is licensed for full

use at a low cost, and collaboration amongst ones colleagues is not only

permissible, it’s encouraged. We saw this as a win-win situation. We

would recoup our cost and invest in further fluorescent protein

research, and our protein costs would not be a barrier to research and

innovation.

The granting of a license to use but not distribute material is not

unique to commercial sources. Although academic material transfer

agreements typically contain specific language forbidding distribution

of received material beyond the recipient laboratory, some researchers

choose to disregard these provisions. Unfortunately through this action

they are disrespecting the intellectual property rights of the original

researchers as well as violating the terms of the legal contract they

signed in order to receive the material. We believe most researchers

choose to respect the great deal of effort that goes into the creation

of research tools for biology and do not distribute any material

received from other labs without their express permission. However for a

company that funds its own basic research our focus is often on the

former example rather than the latter. We believe that this focus

artificially drives up the costs of licensing a fluorescent protein and

obtaining the plasmid, thus we have chosen to believe researchers will

respect our intellectual property as long as we are reasonable in our

distribution which is something we have truly striven for.

Additionally we believe the broad-range usage of a superior, new

generation FP is an opportunity to advocate newer technologies that can

be enabled by mNeonGreen, together with a number of Allele’s other

fluorescent proteins (such as the photoconvertible mClavGR2, and

mMaple). These new imaging technologies are called super resolution

imaging (MRI). They provide researchers with a much finer resolution of

cellular structures, protein molecule localizations, and

protein-protein interaction information. We have started the

construction of a dedicated webpage to provide early adopters with

practical and simple guidance, click here to visit our super resolution imaging portal.

Wednesday, May 1, 2013

The Development of mNeonGreen

Labels:

cell imaging,

fluorescent protein,

FP,

GFP,

mNeonGreen,

Superresolution

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment